A “glaze” in ceramics is a covering of glass on the surfaces of a ceramic object. Although that might sound straightforward, there can be a hidden world in those surfaces. There are many technical publications on the subject of glazes and this is not one of those. A potter applies glaze to a pot. That glaze consists mostly of naturally occurring, mined and processed minerals. Then she puts it in a kiln and brings it to a certain temperature in a certain atmosphere at a certain rate of temperature increase, then cools that kiln at a certain rate for particular effects, all contributing to the end result. Many glazes are very “forgiving”, they will turn out how they are “supposed to” with not much regard for all these firing variables except the final temperature, more are less. There are many reasonably attractive, predictable stable, well behaved glazes available, but most readers might agree that almost all are, well, a little boring, in and of themselves.

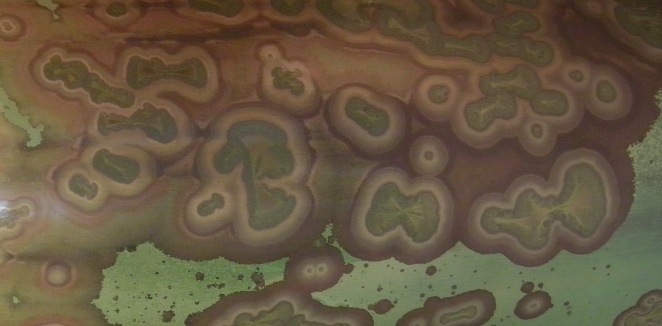

Traditionally, art scholars have had a hard time describing exactly what “art” is ( Adajian, Thomas, “The Definition of Art”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy), but a common thread to all definitions is that all art is “man made”. I am going to try to unravel that thread by claiming that the use of ceramic glazes which may depend on chemical events uncontrolled by the potter are nevertheless an art form. The most interesting glazes are more fickle, the finished product catches phase changes from amorphous to crystalline, there are segregation of colors and textures that tend to be unpredictable, and glaze flaws are endemic. This is a phenomenon that chemists call “phase separation”, that magic area between liquid, solid, crystalline and amorphous, that is captured when the glaze is “frozen” by the cooling of the kiln. The potter is not doing all the creation, she is depending not only on the makeup and preparation of the glaze, but also on partly random events, controlled chaos and the behavior of melted minerals in an imprecisely controlled environment. It is a little like just accidentally on purpose being at the right time and place to see a rainbow across a river canyon. Is that act “art”, with respect to the observer alone?

Is not appreciation on the part of the observer half of what art is? Some people appreciate a sunset and others do not. Is that appreciation of the sunset part of the phenomenon of art, just as is the appreciation of the Mona Lisa on the part of the observer? Underneath it all, though, there must be some family of inspiring or insightful thoughts and sensations that is shared by man-made and natural phenomena. What is really different about the two experiences, other than human ego (the illusion of being a separate entity from the rest of the cosmos) of the observer and the “maker”? Much of art in the West is still centered on the ego of the individual, commerce and social class. Michelangelo was a great artist, Picasso was a genius. Andy Warhol was…, well I can’t say, but he is interesting, and worth money! The “artworld” is part of modern language, meaning those experts who define and create “art”.

Our very bodies, including our brains are made of substances (atoms) that were formed in distant stars, long ago. There is nothing special about the elements that make up our bodies, and the elements of a glaze were made by the same process. The elements, compounds and life evolved and forged what we are and everything around us. We are, almost without doubt, either an accident or an inevitable consequence of a much larger reality. Each of us is a biological being, with a history of at least 13.7 billion years, if you believe the scientists who have been studying this for only the last 100 years, which I do. We are also social beings, we must belong, be shaped by and shape others, survive with others, not completely unlike ants, honeybees and wolves. I do not intend this as any kind of mystical statement, it is just an understanding based on the best current evidence.

What Purpose does art serve? It serves to create a connection between the observer and a phenomenon. It could take the form of aesthetic delight, triggering curiosity, insight, understanding, something that has value to the observer. This connection can be a man-made entity (art) or something in nature. The difference is only in our egos as humans, competing for status within a community, which is part of our nature. On the deepest human level, we are forced by this nature to compete for status among our peers, and in a very fundamental way that is what the modern “artworld” is all about. If Paris Hilton buys your vase, you are an artist, if Joe Sixpac buys your mug you’re a vendor. You and I may not like this, or maybe we do, but tell me how this is not true at the beginning of the 21st century.

What really counts in these experiences, in my opinion, is that precious connection between the observer (Paris Hilton or Joe Sixpac or me standing in a river canyon) and the object (The vase, the mug, the rainbow). Can anyone explain to me, without reference to human ego or commerce how any of these experiences are fundamentally different from one another?